At Gombe National Park and Mahale Mountains National Park in Western Tanzania, Chimpanzees were observed to follow a seemingly puzzling feeding behavior. Within an hour of leaving their sleeping nests, before their first big meal, these animals carefully and slowly selected leaves of specific plants such as Aspilia rudis, A. pluriseta or A. mossambicensis before swallowing them. What was puzzling was, while the chimps chewed and ate most other leaves that were part of their diet, these leaves were taken whole. The animals selected each leaf by feeling it with lips while it remained attached to the stem. The selected leaves were then folded into length wise sections and then swallowed. Phytochemical examination of the leaves revealed the presence of Thiarubrine A. A polyacetylenic intensely red compound, it is highly unstable in light and in gastric pH. Thiarubrines B, C, D, E also have been identified from several other plants known to be antibacterial, antifungal and anthelmintic. In vitro and in vivo experiments of thiarubrines established their nematocidal activity and the quantity of leaves consumed by the chimps was proposed by Rodriguez and Wrangham to carry the sufficient dose of thiarubrine needed to kill their intestinal nematodes.

Leaves of several other plants such as Lippia placata, Ficus exasperata, Commelina sps were among 19 different plants reported to be swallowed whole by chimpanzees. However, these leaves were not shown to contain thiarubrin and obviously the animals were consuming leaves from plant groups with varying chemical composition, many of them with no antiparasitic effect. In other words, there seemed to be no common chemical denominator for these taxonomically diverse plants that were being swallowed whole.

What followed was extensive physical and chemical examination of samples consumed by chimpanzees, their range of nematodes and their life cylces, fecal examination, and so on. A startling observation was made from inspection of fecal samples of chimps that consumed whole leaves. Several worms of Qesophagostemum stephanostomum were firmly stuck between intact leaf folds that were excreted out whole in the feces. These worms had to be tugged by tweezers to separate them from the leaf. It was then realized that rough texture and presence of short flexible leaf trichomes had enabled the worms to be stuck to the leaf and remain trapped within the leaf folds as they passed out of the intestine into the feces. So this “velcro” effect—as Huffmann called it, was helping the purging of whole worms as the leaves passed undigested through the intestinal tract of chimpanzees. Later, leaf swallowing was observed in 11 different species of chimpanzees ( Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii, P. verus, etc.), Bonobo monkeys ( Pan paniscus) and lowland gorillas ( Gorilla gorilla graciers).

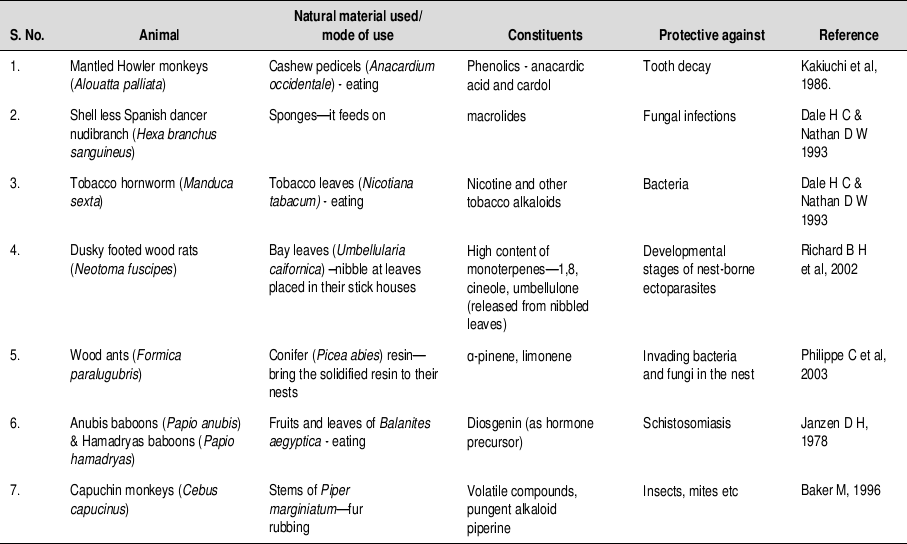

Table 13.1 Zoopharmacognosy—Some more reported observations

The rough surface texture of the leaves swallowed was the common determinant that hooked worms out. Also the roughness of the leaves swallowed on an empty stomach stimulates diarrhea and speeds up gut motility, further helping to shed worms and their toxins from the body. Huffmann deduced that removal of adult worms, made the larvae emerge out of the tissue, relieving general discomfort.

This was the first meticulous observation to be reported scientifically that showed how chimps were resorting to planned self-medication to rid themselves of resource draining worms.

There have been other reports of Tamarins—squirrel-sized, new world monkeys, swallowing large seeds that effectively dislodge and sweep worms out of their intestinal tract.

Leave a Reply