The pneumococcus bacterium played an important part in the discovery of the genetic role of DNA. A slimy, glistening polysaccharide capsule normally surrounds a pneumococcus. This outer layer is essential for the pathogenicity of the bacterium, which causes pneumonia in humans and other susceptible mammals. Mutants devoid of a polysaccharide coat are not pathogenic. The normal bacterium is referred to as the S form (because of its smooth colonies in a culture dish), whereas mutants without capsules are called R forms (because they form rough colonies). R mutants lack an enzyme needed for the synthesis of capsular polysaccharide.

In 1928, Fred Griffith discovered that a non-pathogenic R mutant could be transformed into the pathogenic S form in the following way. He injected some mice with a mixture of live R and heat-killed S pneumococci. The striking finding was that this mixture was lethal to the mice; whereas either the live R or the heat-killed S pneumococci alone are not.

The blood of the dead mice contained live S pneumococci. Thus, the heat-killed S pneumococci had somehow transformed live R pneumococci into live S pneumococci. This change was permanent – the transformed pneumococci yielded pathogenic progeny of the S form. This finding set the stage for the elucidation of chemical nature of the transforming principle.

The cell-free extract of the heat-killed S pneumococci was fractionated, and the transforming activity of its components was assayed in 1994. Oswald Avery, Colin MacLeod, and Maclyn McCarty published their discovery that ‘a nucleic acid of the deoxyribose type is the fundamental unit of transforming principle of pneumococcus Type III’. Until 1994, it was believed that the chromosomal proteins carry genetic information and DNA plays a secondary role.

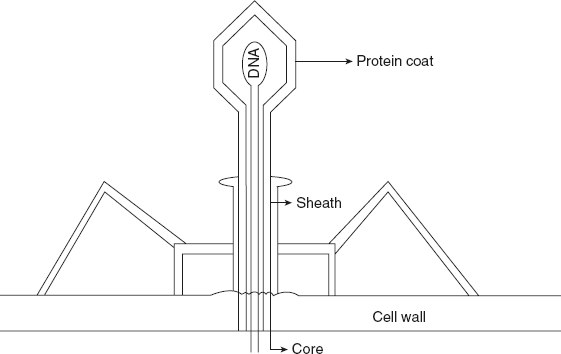

Further support for the genetic role of DNA came from the studies of a virus that infects the bacterium E.coli. The T 2 bacteriophage consists of a core of DNA surrounded by a protein coat. In 1951, Roger Herriot suggested that ‘the virus may act like a little hypodermic needle full of transforming principles, the virus as such never enters the cells, only the tail contacts the host and perhaps enzymatically cuts a small hole through the outer membrane, and then nucleic acid of the virus head fl ows into the cell’ as shown in Figure 5.1.

In 1952, Alfred Hershey and Martha Chase tested this idea in the following way: Phage DNA was labelled with the radioisotope 32P, whereas the protein coat was labelled with 35 S. These labels are highly specific because DNA does not contain sulphur, and the protein coat is devoid of phosphorus.

Figure 5.1 Structural Overview of T2 Phage

A sample of an E.coli culture was infected with labelled phage, which became attached to the bacteria during a short incubation period. The suspension was spun for a few minutes in a Waring Blendor at 10,000 rpm. This treatment subjected the phage-infected cells to very strong shearing forces, which severed the connections between the viruses and the bacteria. The resulting suspension was centrifuged at a speed sufficient to throw bacteria to the bottom of the tube. Thus, the pellet contained the infected bacteria, whereas the supernatant contained smaller particles. These fractions were analysed for 32P and 35S.

The results of the experiments were as follows:

- Most of the phage DNA was found in the bacteria.

- Most of the phage protein was found in the supernatant.

- The Blendor treatment had almost no effect on the competence of the infected bacteria to produce progeny virus.

- This experiment also confirms that DNA is the genetic material of life.

The nucleic acids have been the subject of biochemical investigations since 1871, when a twenty-two-year-old Swiss physician and chemist, Friedrich Miescher, isolated a substance from the nuclei of the pus cells and named it as nuclein. This substance was quite different from carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. Later, it was found that the nuclein had acid properties, and hence, it was renamed as nucleic acid.

The nucleic acid is the hereditary determinants of living organisms. They present in nuclei of cells or in the cytoplasm. They are the macromolecules present living either in the free state or bound to proteins as nucleoproteins.

Leave a Reply