There are thousands of medicinal plant species found in the materia medica of Ayurveda, a tribute to the great biodiversity of the Indian subcontinent. Ayurveda has a unique way of understanding plants, with classic treatises like Charaka Samhita providing an exhaustive description of around 600 plants and their medicinal uses. It contains information on nomenclature, descriptions for identification, biological properties and action, habitat, regional specifications of substitutes and poisonous plants, methods of collecting plants, methods of classifying, combining and processing plant drugs.

Ayurveda has a long history of incorporating non-native plants into its materia medica such as Smilax chinensis (madhusnuhi) brought from China in the 16th century and later mentioned as a treatment for syphilis in the Bhavaprakasha. Drugs are admitted into the materia medica of Ayurveda only after they have been rigorously appraised in terms of their biological properties and systemic action. They are then classified into a therapeutic class and fixed into a set of formulations after specifications are provided for their processing and clinical application.

Charaka Samhita has expounded general principles of drug action based on five factors namely rasa, guna, virya, vipaka and prabhava.

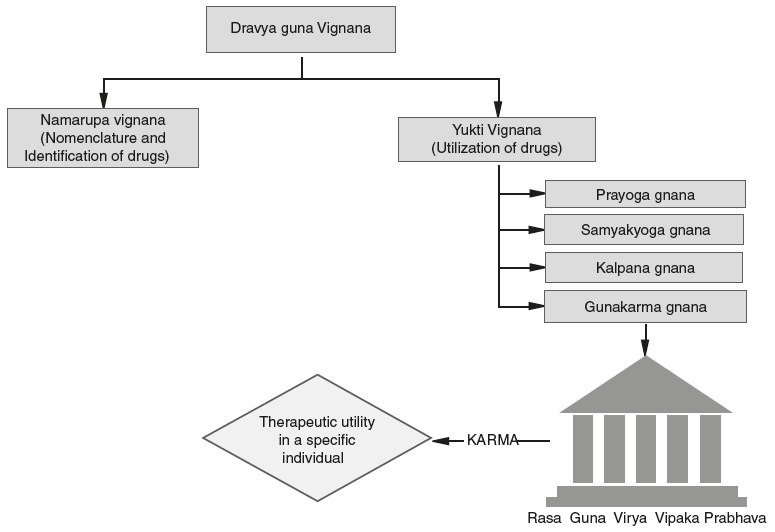

- Dravya guna vignana is the branch of Ayurveda concerned with the medicinal properties of food and medicine.

- Namarupa vignana is a system of mnenonics providing a comprehensive picture of the naming and drug identification system adopted in Ayurveda.

- Yukti vignana is concerned with application aspects and consists of

- Guna karma gnana (actions and properties of drugs)

- Kalpana gnana (pharmaceutical processing methods)

- Samyakyogagnana (incompatibilities, combinations and formulations)

- Prayogagnana (clinical applications).

Guna karma gnana concerned with the knowledge of properties and actions of drug substances is roughly equivalent to modern pharmacology. Padartha is any substance constituted like any other matter in the universe of a combination of all or some of the five universal elements. It is insentient, has no inherent quality and is devoid of consciousness. Conscious use of a padartha makes it a dravya. Dravyas are grouped into different ways in Ayurvedic literature based on their final therapeutic utility, effect upon the doshas, predominance of five universal elements etc.

According to guna karma gnana, medicinal virtue of any substance is described in terms of five essential attributes referred to as the Pancha sheel or five pillars of Ayurvedic pharmacology (Figure 2.3). These are Rasa, Guna, Virya, Vipaka and Prabhava.

Rasa refers to the sensory character of the dravya. Based on perception through the tongue a dravya could be categorized into six rasa types depending on the predominant taste it elicits. These are madhur (sweet), lavana (salt), katu (pungent), kashaya (astringent), amla (sour) and tikta (bitter). Anurasas are tastes that are difficult to ascertain or are tasted secondarily. They add to the overall activity of the dravya though weaker than the primary rasa. It is to be noted that the classification of a rasa is not static due to changes occurring to the dravya over time, including processing and storage. E.g., ethanol extract (tincture) will add katu rasa to the overall rasa of the crude drug.

Figure 2.3. Ayurvedic principles of drug action

Guna refers to the gurvadi guna of the dravya. Depending on the relative preponderance of the five elements, each dravya is attributed with a set of these gunas. It can be detected from the rasa which is reflective of its panchabhautic composition. It must be understood that each rasa is in general reflective of predominance of any of the five basic elements in the dravya. Though composed of all of the five elements, its rasa enables us to identify the predominant elements in the dravya. Thus each of the six rasas is generated by a specific combination of two different mahabhootas. E.g., madhura due to jala and prithvi (Table 2.3). Thus from the panchabhautic composition, the guna of the dravya is inferred. For example, a dravya with madhura rasa is of snigdha guna followed by sita and then guru. Likewise lavana rasa dravyas, being composed of prithvi and agni, are guru followed by usna and then snigdha.

Knowing that each rasa is composed of a particular combination of the five universal elements is a process of inference based on observation and experience recorded from innumerable dravya gunas. In other words taste perception helps ascertain the possible combination of the gurvadi gunas of a dravya.

Virya is the specific potency by which a dravya acts, based on its guna. Though each dravya is associated with a set of gurvadi gunas, the three primary gunas (upakarmas) which are preponderant in each dravya indicate its Virya. Or in other words the primary energetic or predominant gunas or qualities of a dravya refer to its virya. Thus amalaki fruit has a definite amla rasa (ap and teja) with ap being predominant. Hence its virya is sita and as a cooling remedy amalaki is used to treat pitta. Its agni constitution corrects digestion normalizing agni. Here the primary ap is predominant over tejas. Likewise haritaki fruit (Terminalia chebula) has a kasaya rasa. Of its vayu and prithvi composition vayu being the predominant primary attribute, its virya is usna. Thus the fruit hastens digestion at the same time countering the sita virya of vata.

Sometimes a drug is neutral in quality with neither of these being especially predominant. In this case the secondary or non-primary energetic attributes become the primary ones. The virya of the dravya is then ascertained based on these non-primary gunas. In general the degree of exceptional characteristics that a given dravya displays is often proportionate to its usefulness and such herbs that contain contradictory qualities are often a better choice in the treatment of complex disease states.

Vipaka refers to the systemic effect of the dravya post digestion. It describes in part where in the gastrointestinal tract the dravya will exert its activity and how it might affect the doshas within their seats. Simply put, vipaka refers to the effect of the dravya upon the doshas. Since not directly observable, it is inferred by observing its effect upon the body. According to Sushruta, vipaka of any dravya could be of either guru or laghu type. While the former increases kapha and decreases vata and pitta, the latter increases pitta and vata but decreases kapha. Charaka describes vipaka of a dravya to be of three types: madhura vipaka enhances kapha decreasing pitta; amla vipaka enhances pitta, decreasing vata; and katu vipaka enhances vata, decreasing kapha.

Prabhava is the actual physiological effect the dravya has in a specific disease state. More often than not prabhava refers to the tropism of a dravya to a specific ailment. Since it is not logically inferred from rasa, virya, vipaka of the dravya, Ayurveda calls it the inexplicable attribute, achintya. Because it is subject to numerous influences namely the individual’s prakrti, age, diet, heredity, disease stage, etc., it cannot be rationalized within the conceptual framework of dravyaguna unlike rasa, vipaka and virya which are explicable (chintya), i.e., it is beyond inferential thought.

Two drugs having the same rasa, virya, vipaka may have a different prabhava: e.g., Citraka (Plumbago zeylanica) and danti (Baliospermum montanum) have identical rasa, virya, vipaka, but the latter is a strong purgative while the former is not. Thus prabhava describes how certain dravyas seem to display a specificity in action that cannot be matched by another herb which otherwise exhibits the same qualities.

Karma literally means action and refers to the specific therapeutic activity of a given dravya in a specific individual. Thus rasa, guna, virya, vipaka and prabhava are the qualitative indicators which guide in ascertaining the guna karma or actual therapeutic activity in a certain individual. While the latter is patient specific, the former listed qualities are dravya specific. There are approximately 150 types of pharmacological actions (karmas) listed in Ayurvedic literature. These are specific actions that the dravya could exert on the body through different combination of factors. E.g., Langhana (depletion), Brhmana (nourishing), Vamana (emesis), Virecana (purgation) etc.

The therapeutic effects of dravya on different physiological systems form the basis of Ayurvedic pharmacology. There are an estimated 50,000 herbal formulations in the traditional formulae of Ayurveda. Charaka Samhita discusses remedies for several diseases and lists specific drugs. These formulae get modified to suit local conditions by, for instance, substituting the non-principal component (apradhana dravya) with an equivalent either listed in the Sastras or selected on the basis of the principle of rasa, virya etc. From time to time in tune with such an understanding, Vaidyas produce regional texts and manuals that set out recipes for drugs in any given area based on what is available and suitable to the requirements of that area.

Bhaisajya Vyakhyana under Kalpana gnana refers to the principles of pharmacy used in the preparation of a dravya into an oushadi or medicine. It is processed in a certain way to either remove impurities and toxins or to make the medicament more bioavailable etc. Multiplicity of techniques engaged involves the subject matter of bhaisajya vyakhyana. Compared to other medical systems Ayurvedic medicine maintains a relatively sophisticated dosing strategy, dependent upon a number of factors, including the disease being treated and the specific disease underlying the pathology.

Leave a Reply